“I like that performance is slightly more provisional. Not such a beautiful finished object. Unlike an object, it is a process that invites people to ask questions and get involved.”

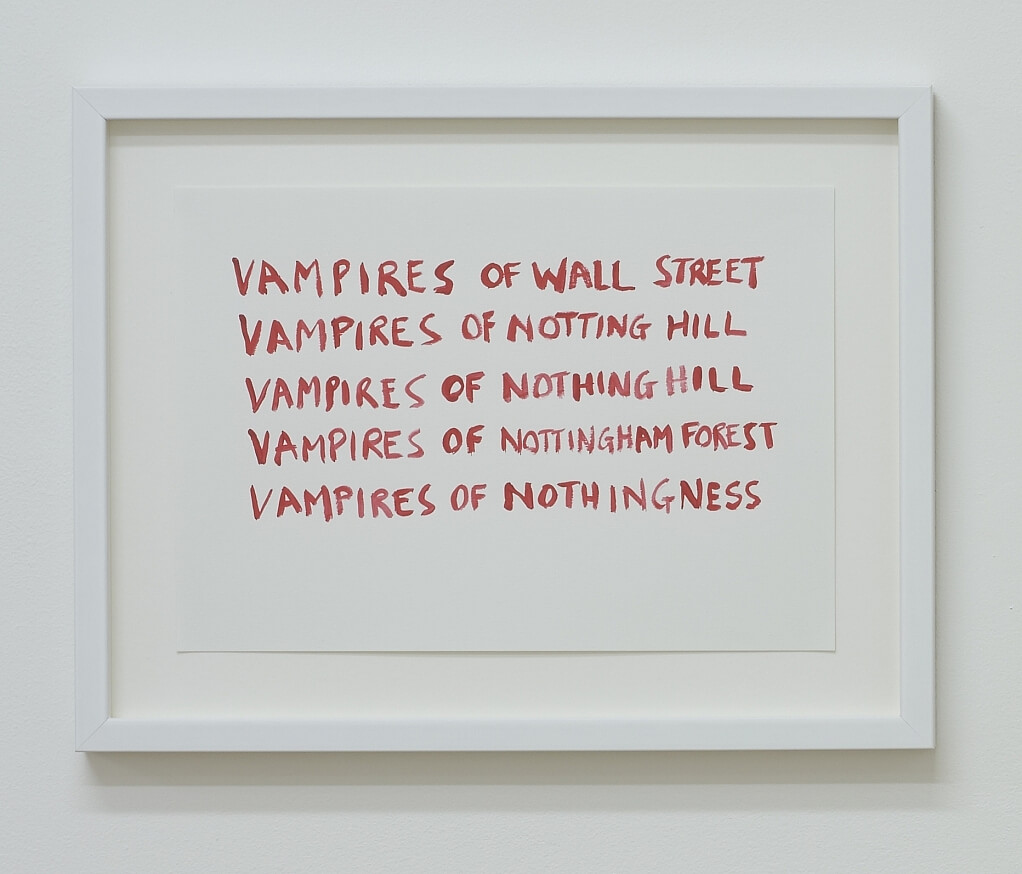

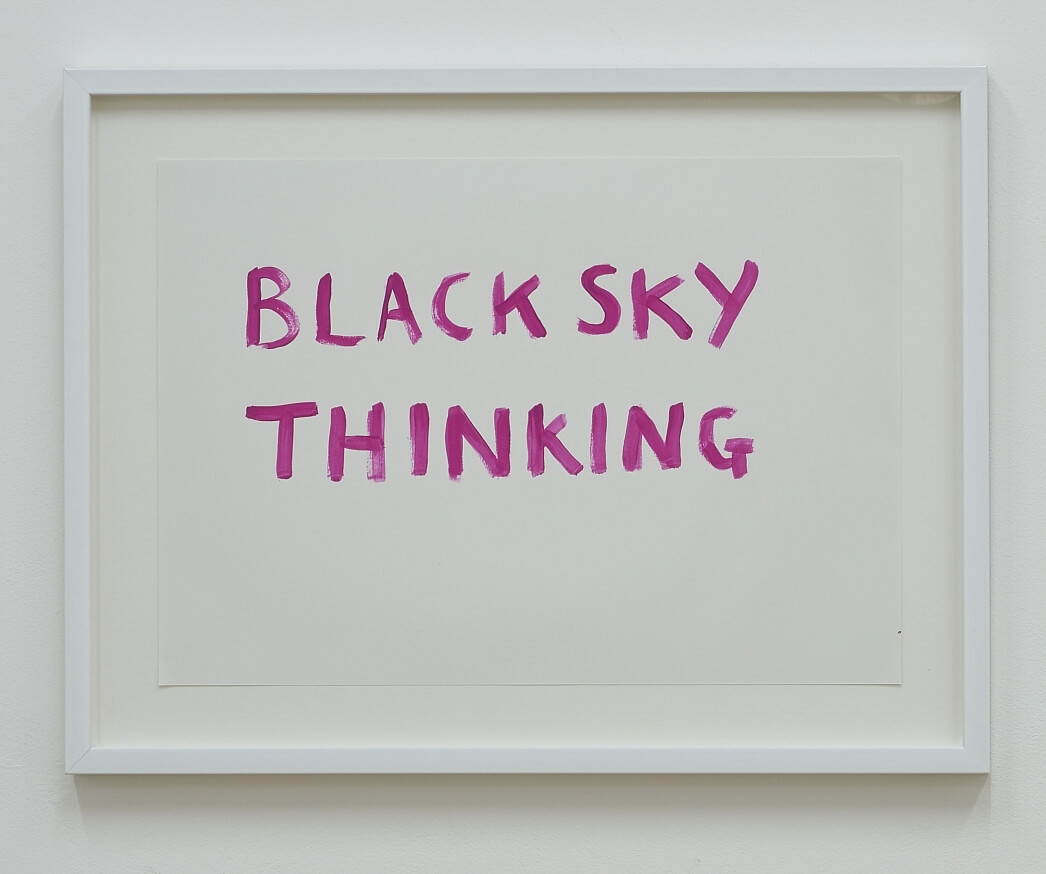

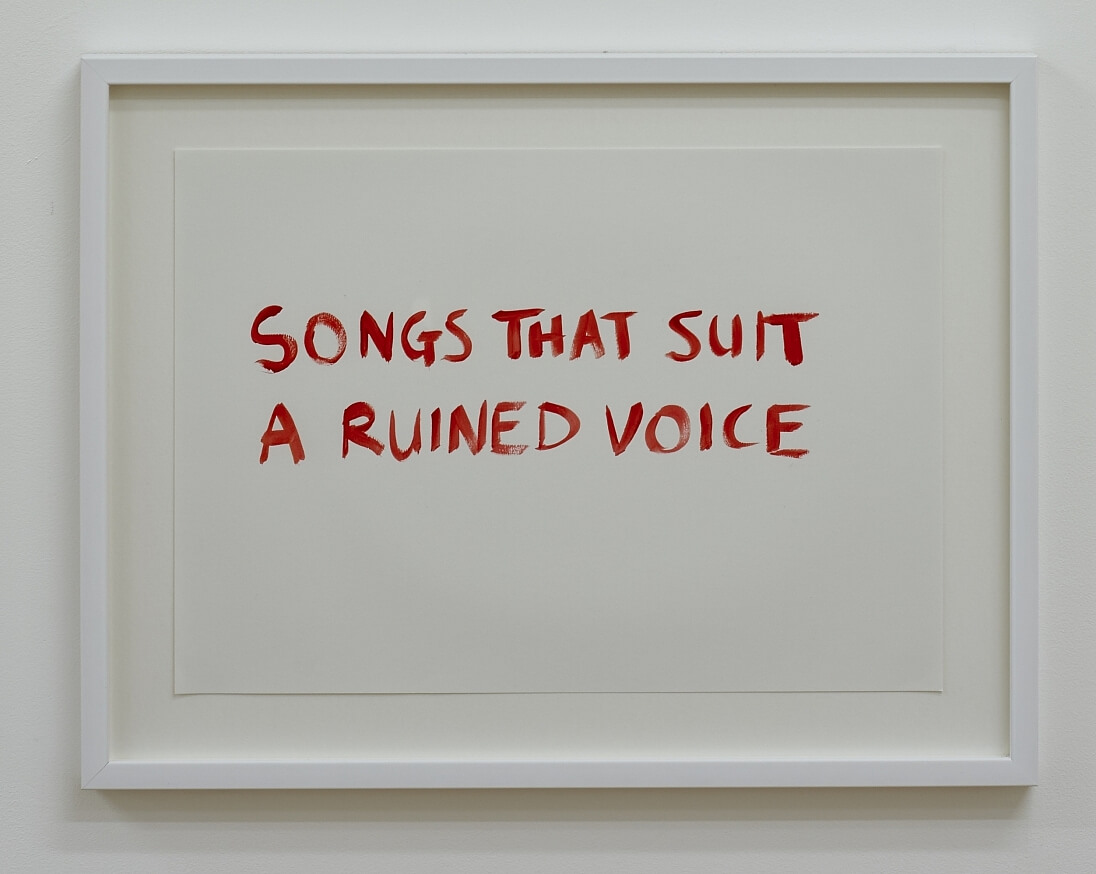

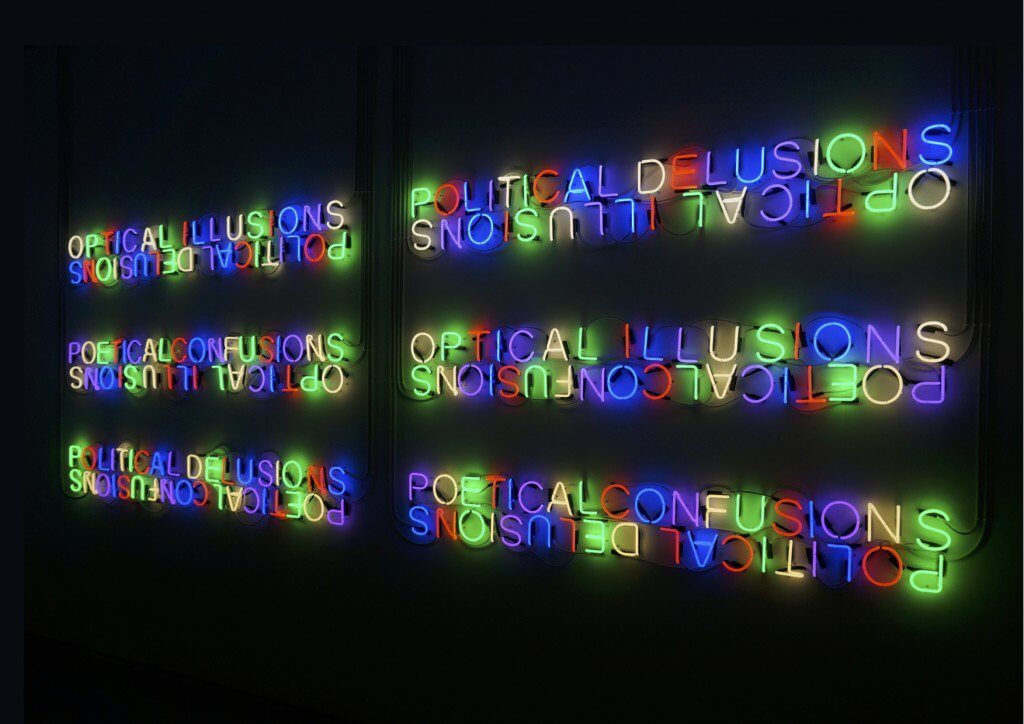

Tim Etchells (b.1962 Sheffield, UK) has led the theatre group Forced Entertainment since its inception in 1984. In 2016, Etchells was awarded the Spalding Gray Award as well as the International Ibsen Award for his work with Forced Entertainment. A $20,000 commission to create a new work and 2,5 million Norwegian Kroner (approx. $450.000) are the respective awards. A fearless innovator. A highly-celebrated artist outside Britain and yet to be fully celebrated at home. Etchells performative practice expands into the visual arts with a strong focus on the use of language with text-based neon, writings painted on walls and drawn on paper and scripted audio and video pieces.

“The work with Forced entertainment has been going on since 1984. That is 32 years of working in that field. I began to focus on visual arts towards 2000. It has taken longer to get the profile, the attention and the context for those projects as developed as the theatre work.”

Despite your raising profile after your awards last year and exhibitions at the Hayward in London and projects with high visibility like the one in Times Square in New York, you also continue to exhibit in smaller galleries with less visibility. Why is that?

I like working on a range of scales. I do things that are very high profile in very visible contexts but I also like working on very independent projects. I am always doing both at the same time.

Do you think that by being in the periphery and exhibiting in smaller spaces you get something that you can’t access in venues with more exposure?

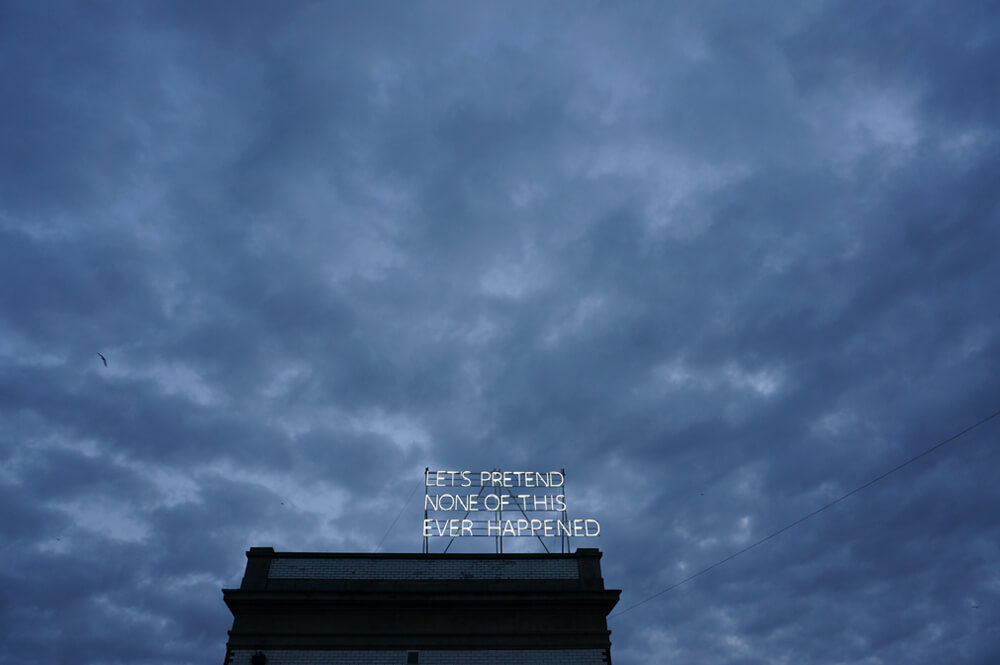

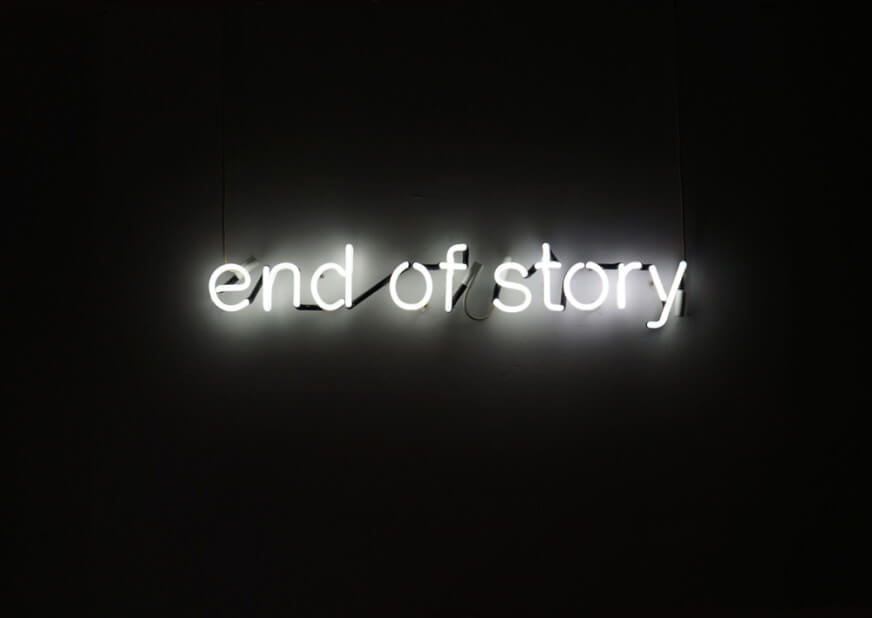

There are different kinds of visibility. If you do something with London-based institutions like the Hayward Gallery or Tate Modern, that is one kind of profile. In terms of critical attention, press and art-world people, it is very visible. But in the last year I also showed works in other places too, I did a solo show in Plymouth Arts Centre and the neon Let’s Pretend, was at The Grundy in Blackpool which looked absolutely fantastic. These shows have less profile but for the public in Blackpool and Plymouth, I think the outdoor neons had a tremendous impact and visibility. Different contexts bring in different focus and kinds of reaction. A show like the Hayward one might lead to more invitations to do other projects but presenting in Blackpool, in terms of the reactions and the intensity of the experience, was arguably stronger because it is not a location with lots of art on offer.

In terms of audience response to performances, you have mentioned in the past that you are interested in the immediate feedback. Do you look for that audience reaction in your visual art practice too?

Yes, in a way, I do. I think about all the work as opening a possibility of connection. I think a lot about the idea of the viewer and the visitor to the gallery; about their role and how active they are in terms of reacting and responding to the work. The work really exists as a means to open that connection.

Do you have your own expectations and speculate about the reactions and the reception of the neon work and text-based pieces?

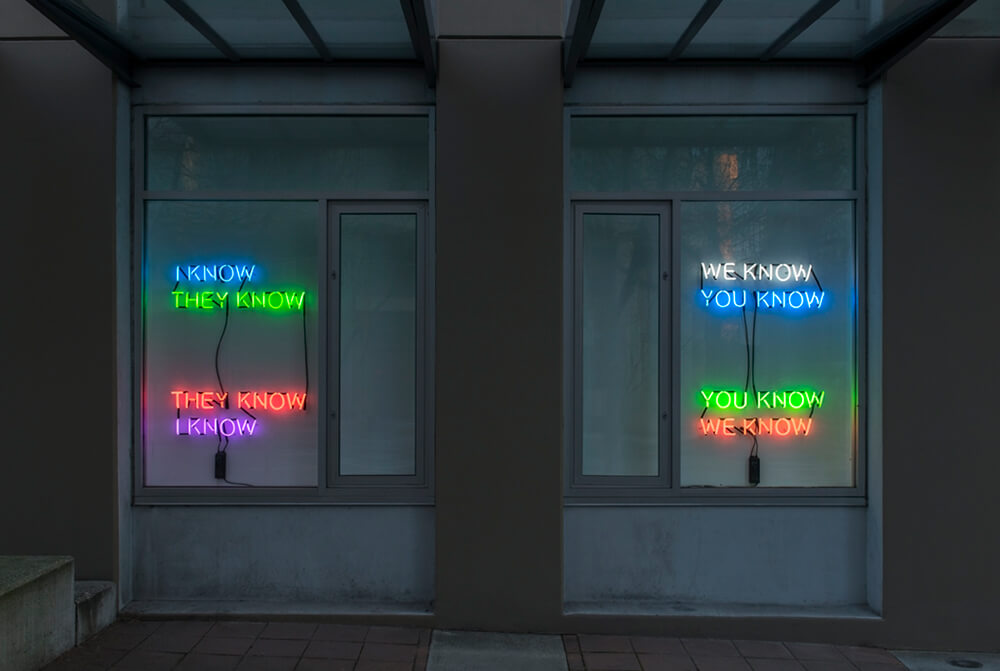

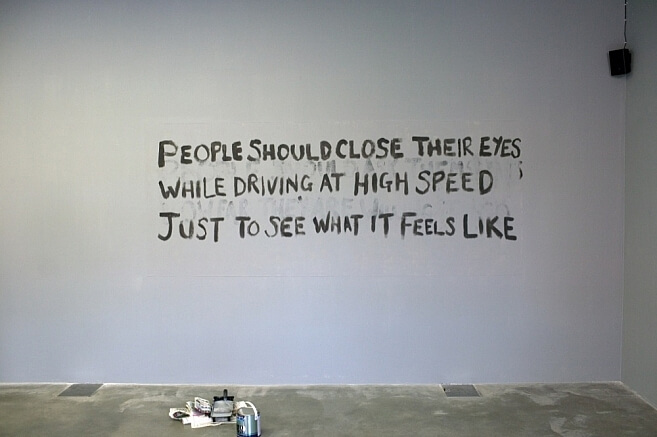

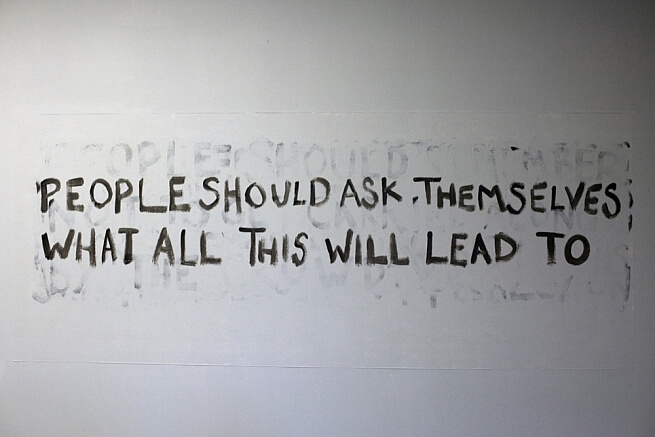

Each one of those works has a kind of atmosphere and constituency, an agenda, if you like. But in at the same time, they are open. Depending how and where they are installed and the context of every viewer, it means something different. For example, Let’s Pretend [the full text for which reads Let’s Pretend None of This Ever Happened] was installed in Blackpool and the year before was exhibited in Bloomberg SPACE in London. Bloomberg is a financial institution in the heart of The City and installing this particular work there brings certain things to mind. When the same work was shown in Blackpool, a very depressed and rundown city, probably Brexit voting, then there is another atmosphere around it.

What I like about the neon pieces is that wherever you put them, they open a slightly different conversation or perspective and, whoever comes, brings in their own set of ideas and thoughts too. I definitely have an agenda with each work, but they are also all made deliberately in such a way that the context and the people looking have the task or invitation to fill in the gaps. They are all porous in this sense, made with a lot of space.

Unlike your performances or your work in the theatre, in your visual art practice you create this direct invitation for a reaction and then you lose connection with that potential response from the audience. How do you deal with that distance?

Maybe one thing that I learnt from performance is the parameters of what people’s reactions are. I think I understand how people read things. Not just text but non-verbal works and responses as well. Maybe from the very direct experience with audiences I have learnt something about what it is to make an open proposition; how people take that and the process of negotiation that people go through when faced with an artwork. Because of that perhaps I feel confident to place works even if I am not going to be there to observe the detail. I think I have a good sense of what will happen – of what kinds of negotiations and readings people will have with the work.

Another part of it is, perhaps, that I trust the work and I trust people seeing it to do what they need to do with what I am putting there. I don’t feel bad about not being around to see the reactions. I don’t control the reactions. I make the work, put it out there and then wait. That process of giving something over is also nice. You have to be ready for that. I always look forward to that.

You have mentioned that you have an agenda. You create text under a structure of dualities and contradictory binaries. They come with a very specific mood and intention. How do these concise and distilled sentences come up?

One basis for my practice is that I collect language. I have a notebook and I am all the time writing sentences or paragraphs. It could be something that I overhear, from a movie or a newspaper or something I make up. They all end up in my notebook. That is a scrapbook that I go to when I am working and I am looking for particular kinds of phrases. I am drawn to combinations of language that are very precise on the one hand and very open on the other. The openness creates a kind of problem or a space and open door that other people can walk through.

For example, in Let’s Pretend, we don’t know what This is. It could mean the XXI century. It could mean Blackpool. It could mean Bloomberg. It could mean just this afternoon, this moment… in any case the work opens up the space for the viewer, it’s the viewer that has to negotiate that. How big is the category? What is being invoked? The work creates a fun space but also a frightening one. Language has this capacity to do that and it allows me to get inside people a little bit.

These works are a distillation of so much significance. Is there a lot of thinking and re-thinking, rewriting and perfecting the piece until is ready? What is your working process?

Collecting is what is important for me. I write down lots of ideas and keep them. When I go back to those ideas, maybe I find one phrase or fragment of language that has a particular quality or heat or openness, or all of those things, that interests me at that moment. I guess that is the heart of the work; it doesn’t matter if the end form for me is performance or written text or video. Working with language in this kind of way is where I have put a lot of my effort through the years. Trying to understand what language is and how it works.

Tell me about your installation Eyes Looking in Times Square in New York last October.

The Midnight Moment project happens every month in Times Square with a different artist and it occupies the time from 3 minutes before midnight until midnight. I always like it when a work is in a public space because people are so used to advertising having a monopoly in that zone. The encounter with an art work can be really interesting, it has no desire to sell you anything. That possibility, to make another use of public space, is great. I was in Times Square for a couple of evenings when they were showing the piece. There were people who had gone there to see it and of course there were others who didn’t know the work was being shown. Watching people’s reactions was very interesting because this work was quite dark compared to the bright and flashy adverts on show.

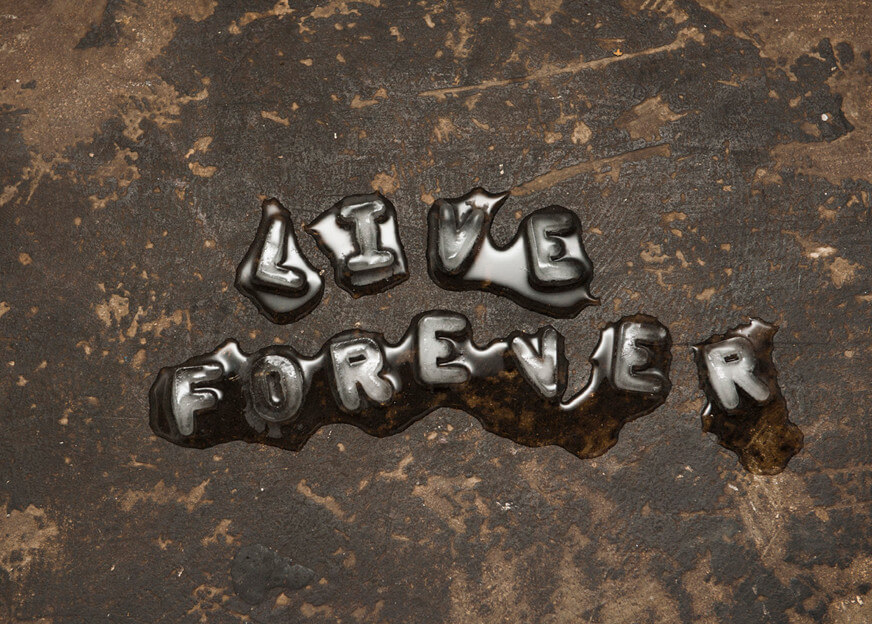

Eyes Looking is filmed on a piece of stone, with letters made from melting ice and although the melting is sped up, it is, relatively speaking, a slow movement. When my work came up, the first thing people noticed, without even looking, was that about 55-60% of the screens became darker. It was a bit like a cloud had passed in front of the sun. You could see people all over the square looking around. It was great! It felt like for 3 minutes the square was quiet. Things slowed down a little bit. It is kind of what I would have wanted, for my work to be on another tempo and a different atmosphere from all the action that is happening there all the time. Almost before anybody read anything, there was already a mood change.

You have said before that you are interested in the potency of failure within language, through the use of contradiction or openness and gaps within the sentences and verbal structures that you create. Has it happened that some of your works have failed in achieving what you set yourself to?

I did one piece in Buenos Aires for a public space and it was a very complicated process with what we had permission to install. I think I had four ideas rejected and the fifth one was accepted. For me the text ended up being too poetic, a little too obscure; like I was hiding something or that it wasn’t totally transparent. I really like the work to be simple. Some kind of internal tension was missing perhaps.

One way I think about those works and about the drawings I’ve done with certain phrases is through my solo performances. In the improvised performances, I think about getting material and phrases out of my notebook in order to understand them, in order to see what they are. When material is in the notebook it is just potential. The performance – speaking the texts aloud – becomes a way of figuring out what the texts might be, what they might mean. I might say the same text 20 times in a performance, always altering the emphasis, the energy, just to see what that feels like, to somehow get to the bottom of it.

What are you working on at the moment?

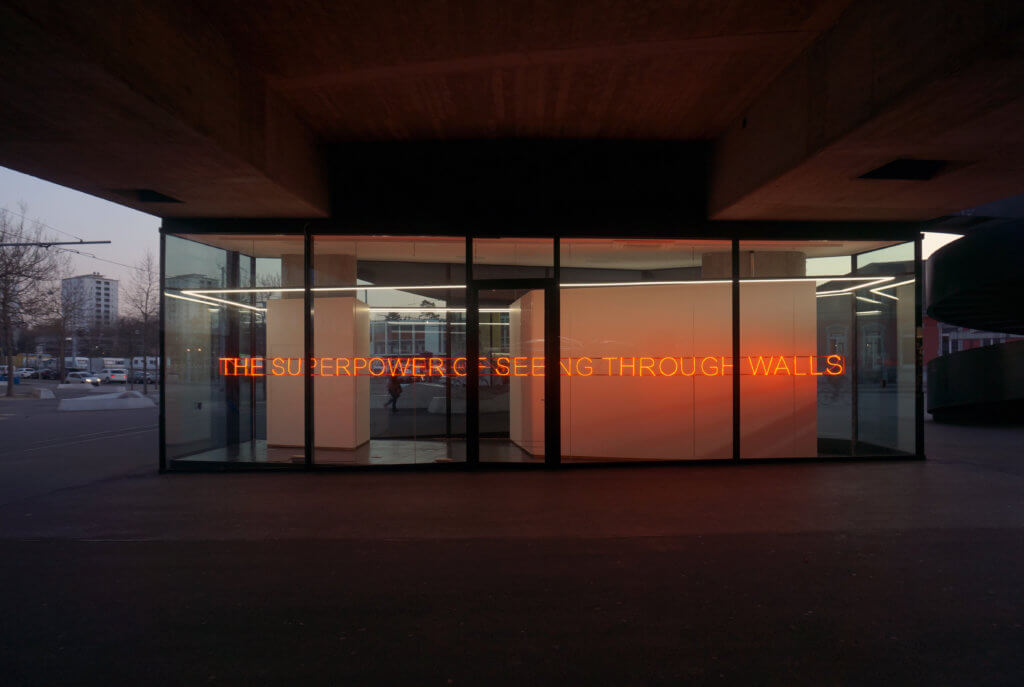

I am working on a sound installation for the Kunstverein Braunschweig in Germany which will open in a couple of weeks. We are working on the audio with lots of phrases that are about metaphors of the body. Phrases like [recites slowly]:

Follow your nose

Keep your fingers out of it

Bite your lip

Hold your tongue

Follow your heart

Lose your head

Don’t lose your head

Pull yourself together

Tear yourself apart

Most of the phrases are imperatives and they all have a strong root or relation to the body. The work began from an earlier piece I made last year, Laugh/Cry, which just uses the phrases ‘laugh your head off’ and ‘cry your eyes out’. These are very violent images and the temptation when you isolate the phrases from daily usage is that you start to take them literally. That is another desire of mine. Often when you take these fragments, they are removed from context so they become literal and metaphorical at the same time.

The new work for Braunschweig, Together/Apart, consists of audio which will run through about fifteen speakers arranged throughout the gallery, carrying very contradictory information [reciting hastily]: pull yourself together, tear yourself apart, pull yourself together, tear yourself apart, tear yourself apart, pull yourself together

It is a little bit like this… [gestures of confusion with hands]. It is about binary oppositions and about creating a state of tension in the viewer. It is also about mapping the inside of the gallery, a whole building, with the inside of the head. It’s a building but it’s also a mental space.

90cm H x 1500cm L x 25cm D

Tim Etchells has currently an exhibition in collaboration with Vlatka Horvat at Millenium Galleries, Sheffield, UK until May 7th; a solo exhibition Open Mind at VITRINE Basel until May 28th and an institutional solo exhibition at Kunstverein Braunschweig, Germany until May 14th

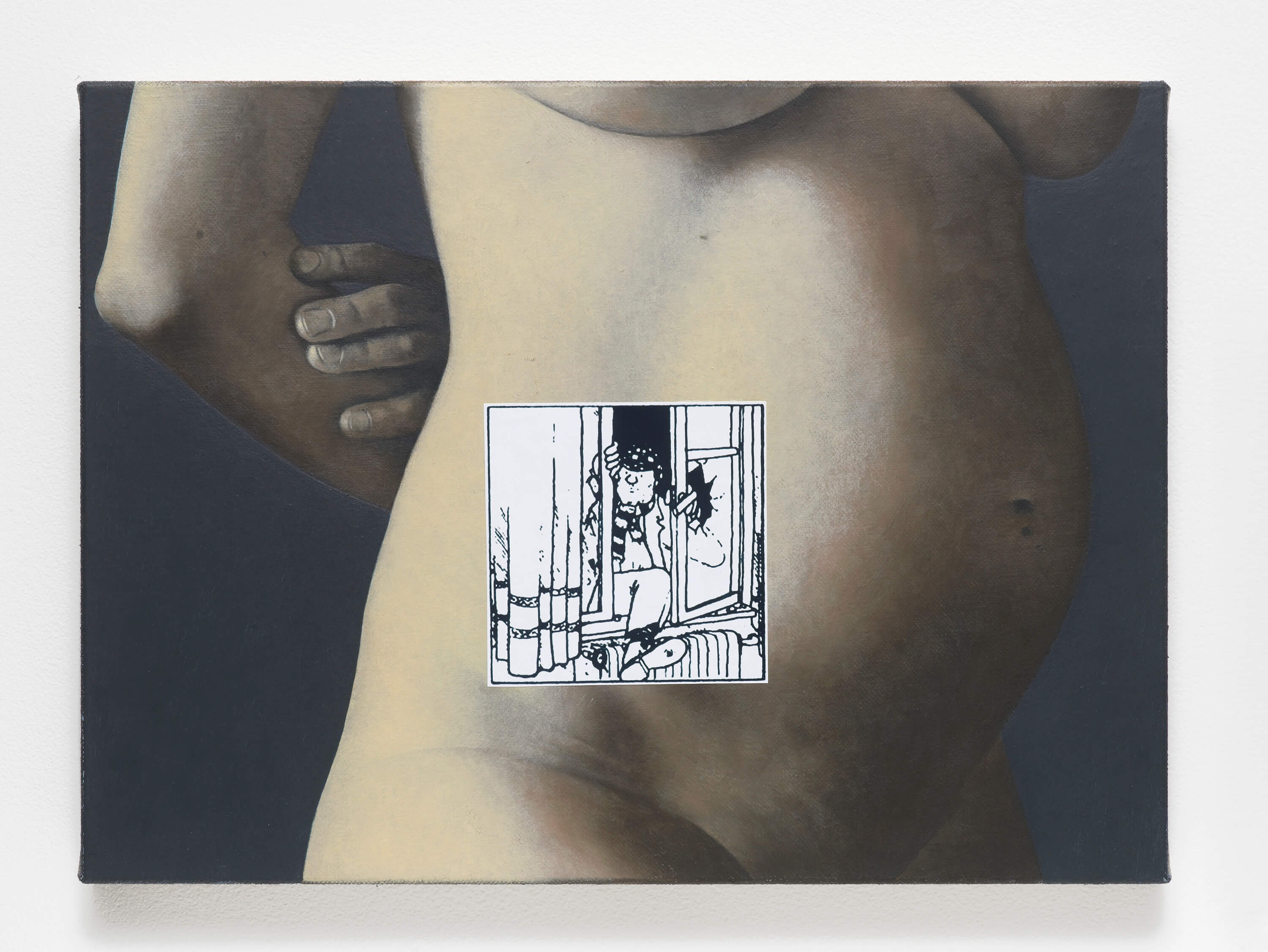

All images are courtesy of the artist.